For the Archive team, January is usually our deep clean month. As part of best practice, we dedicate this time to guarantee that our collections are as well-kept as possible. Dirt, dust and mould are all things the word ‘Archive’ usually conjures up in people’s minds, but all these things are a threat to the physical integrity of our items, and in some instances to the health of our users. Our duty as professionals is to ensure the longevity of things in our care for future generations, and good housekeeping is a vital part of that role.

In previous years you might have seen us around New Court surveying and monitoring our items on display, and not shirking from judicious application of a duster when necessary! Currently this activity is not possible, but we continue to communicate with our excellent colleagues at New Court about our displayed pieces. Communication has always been a key factor in the successful nature of Rothschild businesses; even if business itself was interrupted communication would always find its way to New Court. With this in mind we were reminded of a historical epidemic from nearly 200 years ago which threatened to disrupt the then only form of communication; the letter.

Disinfected Mail

In the early 1990s N M Rothschild and Sons Limited commissioned a philatelic historian to identify important and interesting items with stamps or postal history markings within its Archive. The Postal History final report is of great interest to the Archivists, then and now, revealing to us aspects of the collection we were previously unaware of, including evidence of previous epidemics and the lengths taken to protect the vital communications and people writing them.

The great cholera epidemic of 1830-1831 is well represented within the Archive’s collection. Cholera, an infectious disease caused by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, emerged in the 19th Century. The first epidemic originated in Asia, moving in the 1820s across the continent until in 1829 it reached the Russian border. From Russia, the second cholera epidemic spread to the rest of Europe, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives. By early 1831, frequent reports of the spread of the epidemic in Russia prompted the British government to issue quarantine orders for ships sailing from Russia to British ports. However, the epidemic reached Britain in December 1831, appearing in Sunderland, where it was carried by passengers on a ship from the Baltic. In 1832, the epidemic reached Canada and New York City in the United States and finally reached the Pacific coast of North America between 1832 and 1834.

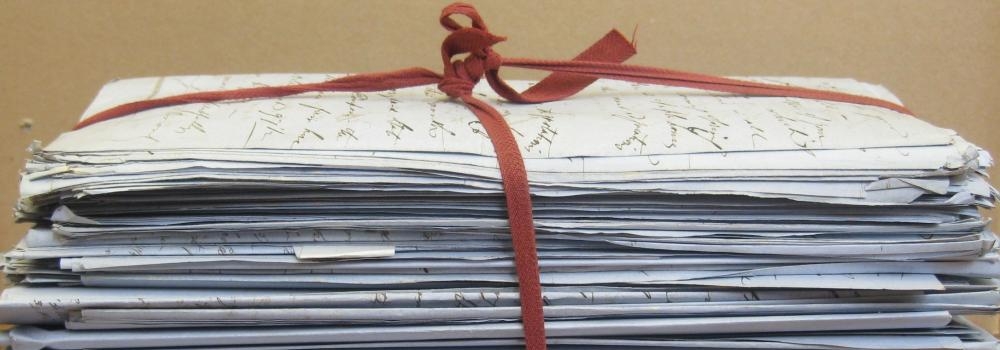

The spread of the epidemic can be followed by the introduction of disinfection facilities at towns in the West of Europe in an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease. Within our collection there are a considerable number of letters from Istanbul (then known as Constantinople) and places on the Asian continent which were disinfected at one of the lazarets in the Austrian Empire or in Malta. A lazaret was a quarantine station, usually for maritime travellers, and where postal items were also disinfected. A variety of methods were used for disinfection, usually the letters were stabbed to allow the fumigation to pass through the letters. A variety of implements were used for this purpose and some can be identified with particular lazarets. One was called a 'retta' which punched a number of small holes over the whole of the document. Letters were then placed in an oven, which accounts for occasional scorch marks, or sprinkled with vinegar, which shows as irregular brown staining.

Letters from the Archive

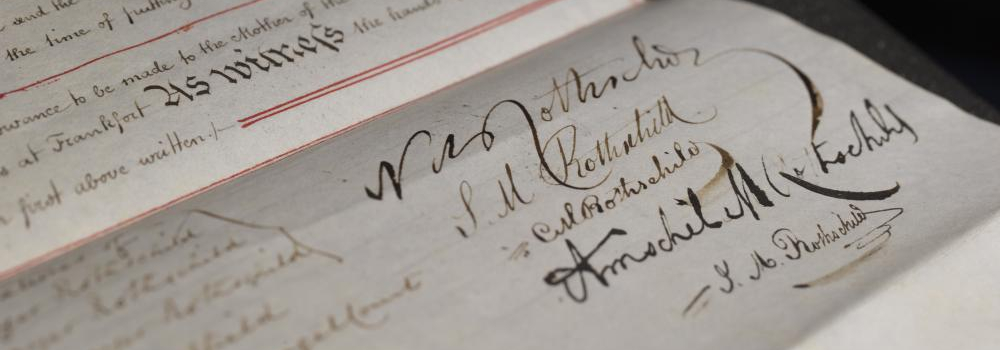

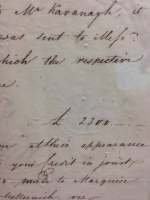

Markings on letters in the Archive, indicate the lazarets at Malta and Semlin, Marseilles, Toulon, Berlin, and Queensborough and Rochester in the UK. Rare markings are also present in the collection such as the ‘Sanst’ markings of Berlin, of which there are a number on the correspondence from F. C. Gasser of St Petersburg. Gasser was a Rothschild agent between 1818-1860 and provided information on the St Petersburg Exchange. A number of the letters describe the actual effect on commerce of the epidemic, but despite this downturn in business Gasser continued to keep the communication channels open. This letter, from F. C. Gasser to N M Rothschild in May 1831, bears stabbing marks made during the disinfection process. Vinegar was thought to offer protection from the disease and appears to have caused some staining on letters when used.

Several letters in the Archive also describe the fear that the epidemic would reach the correspondent’s city as well as the precautions being taken to avoid the disease. A wonderfully vivid example of this is a letter from Salomon von Rothschild, writing from Munich to his brothers on 24 September 1831. Not only does Salomon describe in great detail the latest advice from his doctors regarding the disease, he also makes clear that his responsibility to his business, business partners and clients is always his top priority:

My dear brothers, Amschel, Nathan and James,

I had the pleasure of receiving your letters up to the 19th…

You write that you are sorry that I will not be coming to Frankfurt. Who says so? I will certainly be going to Frankfurt from here, God willing, if the epidemic should not, God forbid and may the dear Lord preserve us from this fate, reach the Frankfurt neighbourhood. But, if Frankfurt is not affected by the epidemic, then even a thousand horses won't be able to hold me back from going to Frankfurt. I would, however, be failing in my duty, my dear brothers, both for myself and for my partners, as well as for the others, if I were to leave this place at a time when I am in the midst of important business negotiations …

My Anselm knows very well how bored I am here. It is almost as if I were locked up and under quarantine. I rarely go out. I don't even go to see any comedies anymore. Because one should not delay entering into a diet until the epidemic is actually upon you, but rather a lot earlier, as all the doctors keep on telling me, I have therefore decided not to eat any more fish of whatever variety they may be. Nor will I eat any vegetables, no vegetables whatsoever. Not even any potatoes. No fat meat. I scrape off all the fat, as one shaves off one's beard, before I eat any meat. No flour based foods, under any circumstances. No dumplings, which is the national food over here. No fresh fruit, be it fresh or cooked. No grapes, no apples and no pears, be they raw or cooked. No butter and no cheese. Very little milk in the coffee, and no cream. I am even giving up my favourite drink, champagne, until the epidemic has completely died out in Europe.

I am already dressing myself in very warm clothes, as if it were in the middle of winter and 30 degrees cold, particularly my stomach and my feet. I am wearing three pairs of woollen socks. Because all the best doctors told me that, as far as infectious diseases are concerned, it is wiser to subject oneself to a dietary regime while one is still healthy, because if one does so at a later stage it is then too late, for one must acclimatise oneself to such a regime while one is still in a healthy state, for once an infectious epidemic is upon us and we only then decide to live according to the strictures of such a regime then, because the body had not previously acclimatised itself to such a regime, it can in fact be harmful, very harmful. I think that my dear family are behaving very wisely when they are already now introducing themselves to this regime, this diet, in Frankfurt, as well as in Paris and in London, and when they avoid the 'night air' and keep their stomachs and feet warmly wrapped up.

If, my dear friends, you were to start getting used to this mode of living [before you are infected by the epidemic], then we will all remain healthy and well, God willing, for I fear that the epidemic will spread throughout Europe. You will no doubt say, "Why is Salomon so scared?" Well, I can assure you it is not fear, but what it is, is that I would be failing in my duty if I were not taking the necessary precautions in advance so as not to blame myself at a later stage that I behaved negligently. After all, it is no more than doing without some small things, and any thinking man must be prepared to sacrifice as much…

Your faithful,

Salomon

As we remain working from home, the deep clean will have to wait until our return but our communication will continue regardless!

RAL XI/38/116B, letter sent in May 1831 to NMR from F. C. Gasser

RAL XI/109/23/8/27, letter from Salomon von Rothschild to his brothers, September 1831